Jamaica’s Plantocracy – Part I

|

|

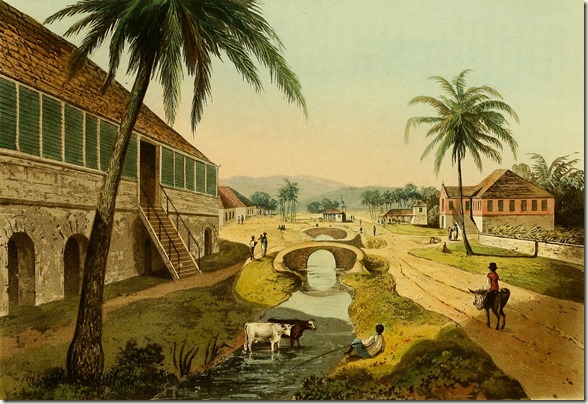

Port Maria, St. Mary’s | Drawn by James Hakewill, engraved by Clarke Published 01 Aug 1825 by Hurst Robinson & Co. |

The earliest European arrivals on the island of Jamaica raised and cultivated a variety of tropical crops and livestock, including cattle and hogs breeding; coffee, ginger, pimento, cotton and cocoa cultivation, and logging. After the British conquest, however, sugar became increasingly important with Jamaica becoming a “sugar island” in the prestige it brought to the sugar planter and in the disproportionate amount of sugar, molasses and rum in Jamaican exports.

Sugar cane was first cultivated by the British in Barbados in 1640 and proved extremely profitable. Jamaica’s sugar industry was established in 1664 by Governor Sir Thomas Modyford, 1st Baronet of Lincoln’s Inn (c. 1620–1679). Colonel Sir Thomas Modyford was a prominent planter in Barbados before being appointed governor of Jamaica. Modyford arrived in Jamaica on 04 June 1664, along with seven hundred planters and their slaves. The new emphasis on the cultivation of sugar cane and its processing into sugar, molasses and rum created the need and the economic justification for a large captive labour force.

I have tended to use the words “plantation” and “estate” in a more or less generic sense. In the early days on the island, “estates” were known mainly for their sugar, and “plantations” were known for other staples, but I often use the terms interchangeably. And, while much of what I describe pertained to life specifically on estates, conditions and traditions were similar on other agricultural properties, whether they were pens, plantations, coffee mountains or the larger settlements.

For much of the 17th and 18th centuries, the British Empire was enriched by sugar production in Jamaica and Barbados, making those islands the brightest jewels in the British crown. And, of course, sugar enriched many planters as well as their European creditors and suppliers. With Modyford’s arrival had come the foundation for Jamaica’s slavery-based plantation society—what we’ll call Jamaica’s plantocracy. In subsequent paragraphs, I hope to give you an idea of what the plantocracy was like and some appreciation for the quality of life under it.

❦❦❦

The timing of Jamaica’s switch to large-scale sugar cane cultivation was fortuitous, for it complimented the British Empire’s plans for economic expansion. The Empire could expand by establishing overseas colonies, and sugar cane would provide the requisite cash crop. But, because sugar cane cultivation needed a large stable labour force, this strategy was not without an enormous cost in human capital. After experimenting briefly with indentured European labour, the British turned to the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Before long, plantation slavery became an integral part of the profitable triangular trade system between England for manufactured goods, Africa for slaves, and the West Indies for sugar and the other agricultural products.

The financial success of that triangular trade system underpinned a colonial society dominated by a planter elite. The plantocracy was fundamental in every sense to the economic, political and social life of the colony.

|

|

Holland Estate, St. Thomas in the East | Drawn by James Hakewill,

engraved by Sutherland Published 01 Aug 1825 by Hurst Robinson & Co. |

Planters owned the best lands and made the colonial laws to support the slave system. Almost all commercial and other economic activity depended on the continuity and success of the plantocracy, the profits that flowed from the sugar islands into Britain, and the commerce generated between the homeland and the colonies. Obviously, not all involved would benefit. The plantocracy, after all, was constructed on a win/lose premise. It was a zero-sum game in which the more the planters won, the more the slaves lost.

The choice of its very profitable sugar-based agricultural economy was not in every way a win-win for Jamaica, especially in the long term. For many reasons, the choice resulted in unintended consequences regarding the efficient use of resources and available technologies.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, the key limiting factor in the economy was agricultural labour, for slaves were always in limited supply. Moreover, sugar cane was so labour-intensive, planters were forced to apply the available labour to the best land, leaving the rest only moderately used or completely unused to cultivate sugar cane. Other factors also limited sugar production: sugar mills were relatively small, and sugar was both heavy and expensive to transport.

Consequently, it is not surprising that by the end of slavery in 1834, there were only about 650 sugar estates on the island, most ranging in size from eight hundred to three thousand acres, so about 650,000 acres were devoted to sugar. Just as this was a small part of the total arable land on the island, the acreage on each estate devoted to sugar was quite small—only about 100,000 acres were actually planted in sugar cane.

Land not suitable or otherwise not used for sugar cane was used as pasture, waste or provision grounds worked by slaves in their off-hours. On an estate of, say, two thousand acres, four hundred or less would be cane fields clustered around the sugar works and mill.

Because it was hard to calculate labour costs under slavery, planters were slow to see the value of labour-saving devices and efficiencies. As a result, Jamaica’s sugar industry inevitably lagged behind mainland England’s agricultural technology. For example, as late as 1830, the plough had not yet replaced the hoe on Jamaican estates.

❦❦❦

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, Jamaican landowners tended to live on the island. A proprietor (or his agent) might have a wife who was from England or Scotland or was a Creole White. For other Whites on an estate, however, a White wife was simply not affordable, for there were never enough of them to go around.

|

|

Montpelier Estate, St. James’s | Drawn by James Hakewill, engraved by

Fielding Published 01 Feb 1824 by Hurst Robinson & Co. |

Bookkeepers who arrived on the island without a wife chose “housekeepers” from among the slaves. Overseers either did the same or made an arrangement with a woman from the free coloured class. Seldom did these arrangements lead to marriage, but many were, nevertheless, life-long unions. The women of these unions were viewed by the slaves as wives and were treated as such by the men. Children of these unions followed the mothers' condition, so children of slave housekeepers were legally slaves. Planters often recognized their coloured children and secured their freedom. Freed children, in turn, frequently bought the freedom of their mothers, if such had not already been done by their fathers. As discussed elsewhere, this practice resulted in three racial classes: White, coloured and Black, which included both freemen and slaves.

The new class of racially-mixed free women and men grew to rival the number of Whites on the island. Some, in time, became land and slave owners in their own right. Because the Whites were so outnumbered by slaves, and because they lived in constant fear of slave insurrection, Whites saw these so-called “people of colour” as natural allies and treated them as such. Whites recognized coloured people as a separate class or caste that was superior to Blacks and gave them more (but not full) rights under the law.

In the United States, where Whites outnumbered Blacks by a wide margin, the just-one-drop legal principle of race classification was practiced. Any person with even a single sub-Saharan African ancestor—that is to say, one drop of Black blood—was considered Black. In Jamaica, by contrast, coloured people were not treated this way. After four generations of marriage to Whites, descendants of coloured people became legally white and enjoyed all privileges and rights of full citizenship. Curiously, in the Jamaica of old, US President Barack Obama would not have been referred to (or accepted by Blacks) as a “Black” man.

Creole Whites and many free people of colour continued to live much as they would have lived in England or Scotland except, of course, for modifications that reflected the reality of their tropical surroundings. In most respects, though, they considered themselves English or British. As the prosperity of Jamaican planters grew, so did their influence in London, which had become the centre of colonial decision-making. Jamaican planters formed associations with London-based merchants and agents, some of whom were responsible for colonial legislation. By 1733, the West India Lobby had grown to include representatives from other major cities like Bristol, Liverpool and, especially, Glasgow. Together, they formed ties with members of both houses of the British parliament, thereby creating a formidable power block, controlling a significant proportion of Britain’s wealth and political power.

The planters and merchants built stately homes both in Jamaica and increasingly in London and the English countryside, with many West Indians rising to high office as city mayors and parliament members. William Beckford, for example, a landowner in Jamaica, was twice Lord Mayor of London. Moreover, in the mid to late 1700s, more than 50 members of parliament represented slave plantation owners.

❦❦❦

As with any industry or commercial enterprise, the economic engines of the plantocracy—estates, plantations, etc.—had a hierarchy that governed them. The chief operating official on a Jamaican estate was the overseer. He made the day-to-day decisions and saw to the discipline and efficiency of the property. The overseer was next in line on the social scale to the landowner—or his agent, who was known as an attorney, who was almost always White or nearly so. Other White workers included masons, carpenters and bookkeepers. Bookkeepers were apprentice planters and often were employed merely to maintain an estate’s ratio of Whites to Blacks as required by the Deficiency Laws. Skilled workers were relatively well-off in Jamaica, bookkeepers less so.

The Deficiency Law placed the responsibility for securing White settlers on plantation owners by requiring them to maintain a certain proportion of Whites to slaves on their plantations. Failure to meet the ratio subjected the planter to a fine. Some planters found it less expensive to pay the fines than to make up the “deficiencies.”

The chain of command continued from the overseer through to slaves who were the “drivers.” The distinction between a “head driver” and a female field-worker was as great as between the proprietor or his agent and a bookkeeper. Next to the drivers were slaves with special skills, the most significant of which was the head boiler. He and the driver assigned to the sugar mill, the boatswain, were in charge of the manufacturing process, including the quality of the finished product. Drivers carried whips as a badge of office and had the authority to use them, which at times they were all too willing to do.

There also existed a hierarchy among properties. The most prominent in economic importance was, of course, the sugar estate. Next were cattle pens, and pen-keepers were second only to the estate owners in prestige. Coffee was second only to sugar as a crop. The other staples were pimento (from which we get allspice), ginger, arrowroot and lumber; however, none of these were on the same level as sugar and coffee. Those lesser crops were grown by small “settlers” on “settlements” or as a sideline on the estates, plantations, and mountains. The organization of pens and plantations was patterned after the sugar estates. Settlements, depending on their size, were similarly organized. And they all depended on slave labour.

We’ll pause here and pick up our story later with more details—some of which you may find surprising—of the day-to-day lives of plantation slaves in our next instalment.

Comments

Post a Comment